The Detriments of Debating Over Blackness

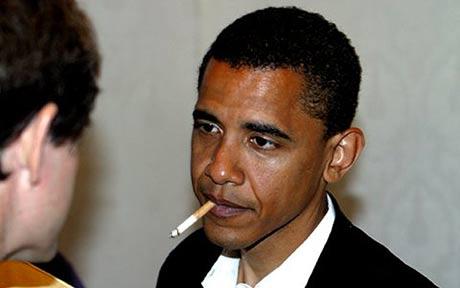

I was on a mini-vacation visiting some old friends who had recently moved to Montreal. After a meal one night, Barack Obama came across the television to give his state of the union address. This started a conversation on Barack’s blackness. One half-English half-Trinidadian girl, a man of mixed tones with accents of Polish and Jamaican ancestry, one African, and another hyphenized female all became engaged in a conversation about race, Blackness, and education. It was my African friend that intrigued me the most. He was from the Republic of Congo and his intersection of race and education way different than me.

He takes the whole idea of education and race and flips it on its head. He feels that the catalyst of the “black male conflict” as he calls it, is due to the need for many black males to rebel against the dominant culture. “Whose idea is it that we need to go to university? Not mine if my family doesn’t have the money for it,” he articulates, trying to make reference to the fact that issues of class and race intersect to create a perpetual system of inequality that is overtly evidenced through the practice of education. He is firm on his stance. Black males don’t care to do well because not doing well demonstrates their agency.

Our discussion got me thinking about race and education and how the two are forever interlocked. Why must we do well in school and get good grades? Why must we study the subjects that we do, or even learn about the things that we are learning about? Although demographics in almost every major metropolitan city have shifted over the last 50 years, how come we still read about the same authors and “monumental” figures that are all predominately white? My friend from the Congo says that the dominant culture has determined the things that we think are important in society, but just because they have decided on these things doesn’t mean that we all should simply tag along. They have decided what type of dress is suitable and what type of dress is not; must we all play dress up from Monday to Friday, and even Saturday if we are to be taken seriously out in public? Many teachers wear running shoes to work. I do as well. But how come my selection of running shoes elicits comments every time I walk down the hall? “Oh, I like your shoes! Are they new?” a polite, yet intrinsically naïve teacher will ask me as we cross paths in the photocopy room. From the gazes and the comments I feel compelled to conform, even in the area of picking running shoes!

Are the Jordans I wear and the Nike’s that “Steve” adorns not both classified as sneakers? But one seems to be a bit less professional for some obscure reason. Why is it so easy for the dominant culture to be comfortable, and so hard for others who have to work each and every day at not only doing their job but also proving that they are “worthy enough” to be included. Most cultures walk, talk, and in all honesty, do almost everything else different, but one culture holds the rights to the politically correct and professionally superior conduct of what we deem as “universal”. Not fair says my friend. So forget it all, he says. “Do you and see what happens,” he claims, “because either way it is going to be hard, so you midaswell be a little more comfortable for the inevitably bumpy journey”.

As a dark-skin black male, my friend from the Congo has experienced many things that I probably have not. And that is where the core of our differing understanding on race and education lay. Context and opinion are fostered through experience. We come to form our opinions mainly through the lens of our own experience. For him, his views are based on his childhood, growing up in one of the most corrupt regions of Africa where whites are still feared and considered “superior” to blacks and then having that reality juxtaposed by moving to Toronto, as an immigrant, and seeing these same white people, who he had grown to think of them in almost godly terms, on the street corners begging for money. He considers race, education and the interconnectedness of the two in a completely different light than me, a mixed-raced Canadian who grew up in a low to middle class household who experienced some hardships that were relative to the reality that I knew at the time. Two different lives, two different experiences, two varying opinions. But one thing is in common. Black lives matter but society seems to tell us otherwise. Barack’s blackness shouldn’t be up for debate.

And as young teachers we must keep in mind that we instruct through the premise of understanding that our opinions are based on our experiences in life. Someone else may tell you how to do something or handle a situation, and you may think it will help you because they are more “experienced.” But the word “experience” is very fluid. Yes, those veteran teachers are indeed experienced, but guess what, so are you – you are experienced in life, in situations, in understanding context from your perspective and your experience. Your epistemology is undeniable. So for you, do things exactly how you dreamed of doing them, because at the end of the day, that is when the most genuine learning happens – for your students, and arguably as important, for you as well.

[share title=”Share this Post” facebook=”true” twitter=”true” google_plus=”true”]