The transition from the predominantly white elementary school I attended to the largely marginalized middle school was the closest thing to culture shock this “native son” ever experienced. I can recall only ever seeing a handful of other Black bodies in that entire school building from the first grade to the sixth. I thought about getting my hair cut like Jonathon Taylor Thomas, Nick Carter, and the other teen bop celebrities of the ’90s. But I stuck with the low buzz fade instead of going for the trending “mushroom cut” because I knew my hair texture was not like their hair texture.

In fact, I had little in common not only with those celebrities but also with my peers. We might have learned the same things while sitting in the same classrooms together and played sports during recess, but my friends and I lived in different worlds. We were obligated to participate in the same institution of education and loosely follow the same rules that society dictated for us as kids — but that’s where the parallels stopped. Ironically, what I went through at the beginning of my “educational career” as a young student was almost identical to what I went through at the beginning of my career as a teacher.

For the majority of my first years as a teacher, I came to school without a lot of things. I left my earrings out for the first few months. I left the clothes I considered “normal” for me to wear and then went and bought the things I thought fit the “traditional” teacher uniform: khakis, plaid shirts, boat shoes. I listened to talk radio on the ride into work instead of to the hip-hop music I was accustomed to having accompany me while driving. I did so in order to leave my accent at my door and to adopt a more “conventional” communication pattern. I was habitually conscious of making sure the tattoos on my upper arms remained covered. Essentially, I came to school without my authentic identity — because of what I had internalized about what words like normal, traditional, and conventional meant to the majority. Even though I was Black, I was carrying the same “legacy baggage” that came with being a so-called teacher.

Things within education and public schooling have changed since I was a student. Fortunately for me, it’s not hard to juxtapose the past and present: I’m teaching at the Toronto school I went to when I was a kid. Not the elementary school I entered my educational journey with or the high school I ended my public schooling with, but the middle school. It’s there that I learned just how racism still operates in the school setting. It’s a cold, hard, and ugly truth — one I know because I have seen racism from both sides of that teacher’s desk.

Although policies, procedures, and practices have changed, much of the core philosophy behind pedagogy has not. For example, the teacher diversity gap — which is basically the percentage of racialized teachers compared to the percentage of the general population that is racialized — while still abysmal, has narrowed slightly since the late 1990s. I could use statistics to support this point, but I would much rather use experience, since part of why racism still permeates the institution of public schooling is that the academic community has consistently relied on data over experience. I know that the teacher diversity gap has lessened because, when I was a student at my very, very racially diverse middle school, all the teachers were white. Twenty years later, as a teacher at the same — and still, very, very racially diverse middle school — almost none of the teachers are white. Yet racism still runs rampant throughout schools just like mine. Clearly representation alone does very little to extinguish it.

But what about actual policy? Or the tangible shifts in pedagogy? We have changed our policies on discipline, achievement, teaching, and training over and over, yet, from the time I was a student until signing off this past June on my ninth year as a teacher, I can testify to having witnessed, experienced, and read about racism in schooling. So what has, or hasn’t, changed?

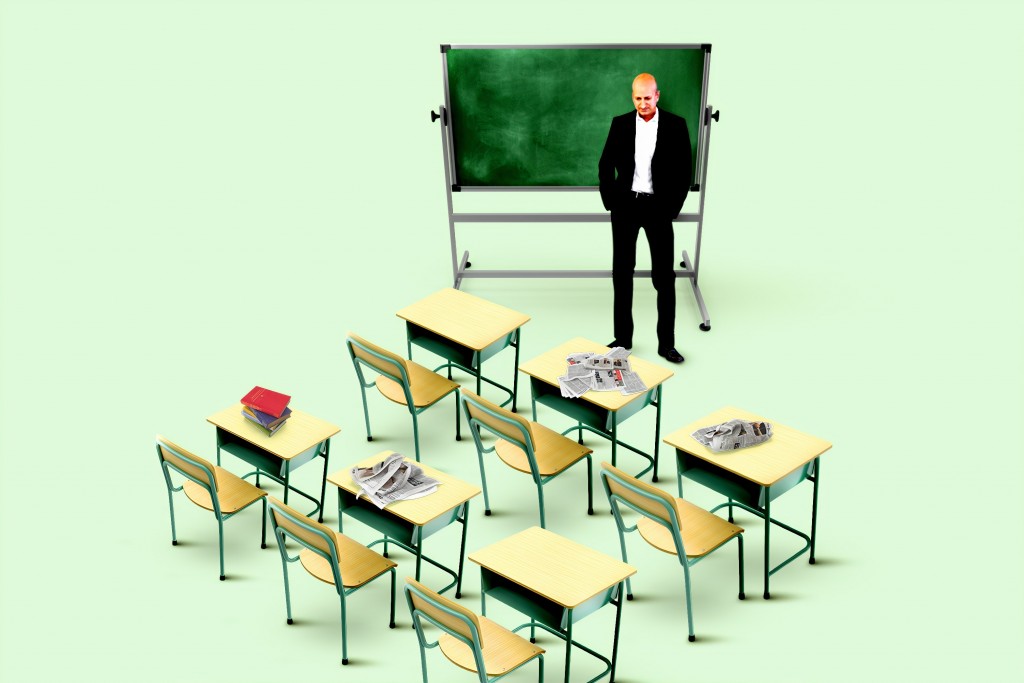

Despite important advancements, improvements, and changes that make for a more equitable public-education system, most of the general thoughts surrounding public education have continued to support the status quo. Most glaring is the legacy pedagogy baggage that the majority of teachers carry around. Today, you may walk into a typical classroom and no longer see chalkboards or desks aligned in rows. You may not even see textbooks. You most likely will see teachers who look completely different than the teachers who once taught you.

However, if you hang around long enough, and look close enough, you may notice that almost nothing new has been created. Generally speaking, teachers teach the way they were taught to. Similarly, schools still measure and subsequently validate intelligence through deformed definitions of the quote-unquote universal student. There are still kids getting reprimanded for chewing gum, for not putting their hand up to answer a question in class, and for wearing their hat in the hallway. Yes, we have made changes. But changes to structures don’t always beget changes to mindset. When it comes to anti-Black racism, an inequity that still deeply infests my profession and has plagued public-school systems since my time as a student, this fact is crystal clear to me.

I often used to hear my aunt say, “I’m just taking off the talk and leaving the whispers.” She would say that while she was cleaning in reference to making her home presentable, tidying up. Take off the talk and leave the whispers. When we update policies, practices, and pedagogy, this is essentially what we are doing. It is important to keep the house of education tidy and presentable. But clean floors and fresh tablecloths don’t count for much if there’s damage to the home’s foundation.

We may wonder why, given all these changes to education, things have stayed so much the same — especially when it comes to racial inequities. Well, changing surface elements does not eliminate racist thinking. Tidying up does not get rid of the boogeyman of racism that lurks under the beds and in our closets. There are still silent assumptions that have not changed in my 20 years of being involved with school in some form or fashion, the most prominent one being that academic excellence in public school always gets back to notions of cultural assimilation. If we truly want to see change, especially in regard to anti-racist education, we must be aggressive about what we consider racism, analyze why we consider it racism, be brave enough to have these conversations, and implement real policy and practices that do more than renovate the institution of public education. If we truly want to continue working on eradicating racism in the public-school system, we have to not only get down to the “whispers” — we also have to look at the tools we’re using and work to dismantle the house we are in.

[share title=”Share this Post” facebook=”true” twitter=”true” google_plus=”true”]